ANXIETY NOT REQUIRED (IN ACADEMIC WRITING)

/“I have a lot of anxiety and feelings of inadequacy surrounding my written work.”

Many doctoral students begin their programs with heightened anxiety about their writing ability. No matter how well they have fared in their prior studies or professional careers, they harbor this belief that doctoral-level writing requires much more skill than they possess. And, of course, they are convinced that every single one of their cohorts is at the necessary skill level that they l

I just want to say to them, “It’ll be okay.”

In fact, the academic writing that is causing so much anxiety, if put to the test, would produce a quality of writing that is stiff, arguably dead, and full of unnatural, little-known, seldom-used words (hirsute v. hairy) and vague phrases (there was discord in the household – whatever that means!). Some of your readers might absolutely hate you; you are making them work so hard at trying to decipher what you are trying to say while being distracted by your obvious focus on sounding smart (if not pompous), and consequently, boring them to tears.

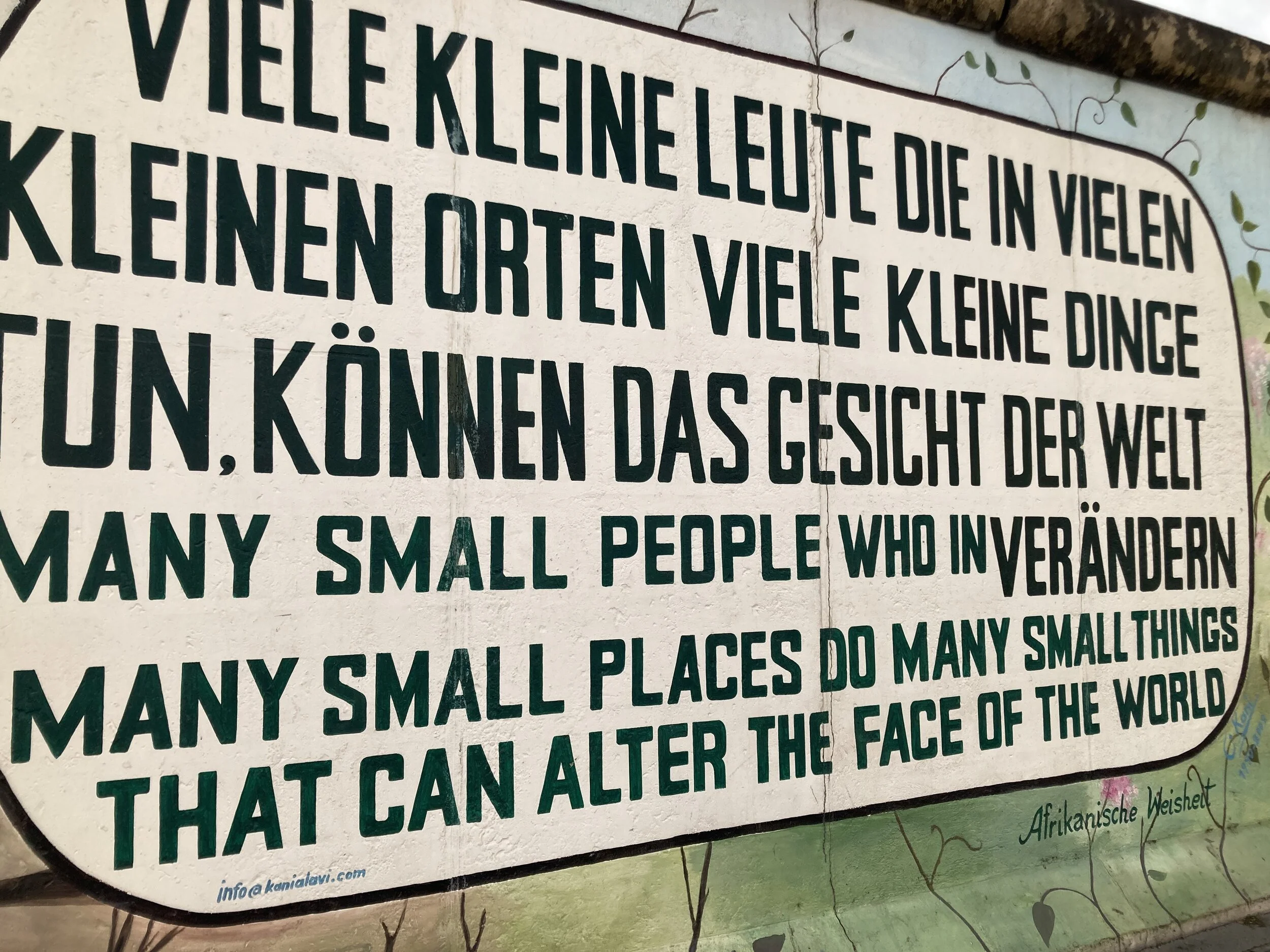

So, let’s step back. The most important aspect of writing is communication. The writing we all love to read is written by someone who is passionate about their subject, and their choice of words and phrases comes from their heart and their natural voice – they are talking to you the reader.

The key words here are natural voice. How might you be talking about “discord in the household” to a friend or colleague? “Yeah, the parents were fighting all the time, about the most insignificant issues: how to properly fold napkin rings or shirts.”

The focus should NOT be on how erudite, highbrow, intellectual, and knowledgeable you are, but rather on whether you are communicating your ideas clearly, succinctly, accurately, and compellingly ... and whether you have something fresh to say that merits being said.

In academic writing, your audience is a naïve colleague. That is, they are unfamiliar with your subject but are otherwise at the same proficiency level as you. Even ESL and international students, although not yet fully mastering a second (or third) language, are able to communicate well with the naïve colleague because they are thinking at the doctoral level.

In the final analysis, it is: How well do you think? And how much thought have you given to what you want to say?

And although we all want to say it well, it is far more important that what we say has meaning and value.

Kathleen Kline is an academic editor with over 35 years' experience editing dissertations, theses, and other academic documents, primarily in the fields of psychology, religious studies, and education. She assists and teams up with students and professionals across the full gamut of writing challenges.

Kathleen is the Director of the Writing Center at the Wright Institute, an APA-accredited school in Berkeley, CA, offering MAs and PsyDs in Clinical Psychology. She teaches workshops in numerous writing-related areas and coaches and assists students with their many written assignments. She holds degrees from Georgetown University in Washington, DC, and The Sorbonne (Université de Paris IV), in Paris, France.

Kathleen is the author of De-Stressing the Dissertation and Other Forms of Academic Writing: Practical Guidance and Real-Life Stories, an affordable no-nonsense guide, addressing many areas of student concerns while navigating their doctoral programs. Kathleen was inspired to write this book as a way to save students from many avoidable challenges and pitfalls, with this simple regret: “If I Had Only Had 30 Minutes With My Clients Before They Started Their Dissertations.”

She is available to work privately with individuals on their dissertations, internship applications, CVs, and other academic-related documents.

You can contact Kathleen at kathleen.kline@sbcglobal.net or 510-339-1629, or visit her website at www.kathleenkline.com.